Nikon FM, 50 mm lens, Ilford XP-2 film.

My youngest niece, Norah Grace, is the one looking confrontationally (or perhaps mistrustingly) at the camera. She's ordinarily quite a ham, but was taking a break from her grin-and-pose normal self.

In the doghouse behind Norah Grace is her youngest cousin, Makenzie, who is obviously grinning like a fool. I guess she's just happy about being able to fit in there.

Gaston Bachelard, in his "Poetics of Space," writes about man's recurrent daydreams of living in uninhabitable spaces, like nests and shells -- places where "in order for us to live them, require us to become very small. Indeed, in our houses we have nooks and corners in which we like to curl up comfortably."

Who doesn't have such a space? For me, it's the ragged old chair next to my desk, where I huddle under a lamp while reading. For one of my former students (at one time I taught Comp. 101 at a community college) it was a window box in her parents' home.

When I was a child, I did much of my best daydreaming in small enclosed spaces, such as the space under the stairs, the "cave" that remained under the rootball of a tree that had fallen in the vacant lot next to a childhood home, a literal cave in the woods behind a later home, and the like.

To return to Bachelard, he says further that "to curl up belongs to the phenomenology of the verb 'to inhabit,' and only those who have learned to do so can inhabit with intensity."

By learning to exist in small spaces, then -- whether literal or psychological -- we learn to exist more fully in larger spaces. By curling up we learn to more completely inhabit our alloted space once we stretch out. By working small jobs as best we can, we learn to effectively manage larger jobs. By writing paragraphs we learn to write essays or stories or novels.

More Bachelard: Speaking of a house in which one lives he said, "if I were asked to name the chief benefit of the house, I should say: the house shelters daydreaming, the house protects the dreamer, the house allows one to dream in peace."

Does Makenzie care what some French philosopher thought about her choice of hideout? I doubt it.

But did Bachelard have a four-year-old hiding in a doghouse in mind when he wrote his book about how humans experience intimate places? It's possible. He writes about the nearly universal human drive to seek out small spots in which to live life, however briefly -- and the universal certainly includes little girls in doghouses.

In this photo, however, both the internality of Makenzie (curled in the doghouse) and the externality of her younger cousin (confronting the camera) are necessary. Either portion of the photo viewed on its own would be significantly weaker than the combination of the two. It's the marked contrast between these two little girls that makes the photo worth looking at. Are these cousins actually that different? I don't think so: Their temperaments are not entirely dissimilar. But the story of life itself is not told in broad, sweeping terms. All stories are told most effectively and interestingly by looking at specific points in the action.

And that's what photography is, especially when dealing with people and other active subjects: a pointed look at one very specific moment in time.

Makenzie won't forever live in the doghouse. She currently lives in Brazil, in fact. And Norah Grace won't always be tiny and fragile. But by learning to exist comfortably and to dream colorfully in these small "spaces," they'll be better equipped to live in the larger world.

Dream well.

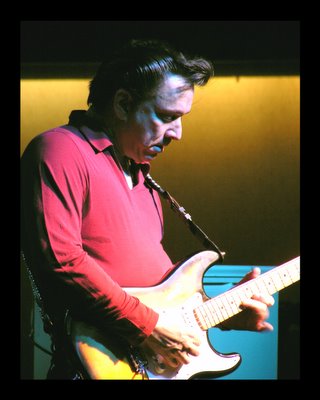

Jimmie Vaughan, formerly of the Fabulous Thunderbirds, played a concert at the 2004 Libertarian Party National Convention in Atlanta, Ga. I had heard only a few of the man's songs and didn't even recognize him when I met him at a party before the concert.

Jimmie Vaughan, formerly of the Fabulous Thunderbirds, played a concert at the 2004 Libertarian Party National Convention in Atlanta, Ga. I had heard only a few of the man's songs and didn't even recognize him when I met him at a party before the concert.